Security

Kerberos

Kerberos is an authentication system used by Anthena. It is a trusted third-party authentication service.

Project Anthena was started by M.I.T. in 1983 and its goal was to create an educational computing environment built around high-performance graphic workstations, high-speed networking, and servers of various types. The operating system for the project is based on 4.3BSD.

Kerberos assumes that the workstations are not trustworthy and requires you, the client, to identify yourself every time a service is requested. For example, every time you want to send a file to a print server, you have to identify yourself to that server. Any system could implement a strict security mechanism such as this, by requiring you to enter a password of some form every time you request a network service. The techniques used by Kerberos, however, are unobtrusive (not noticeable).

Kerberos follows these guidelines:

-

You only have to identify yourself once, at the beginning of a workstation session. This involves entering your login name and password, and is automatically built in to the standard UNIX

logincommand. -

Passwords are never sent across the network in cleartext. They are always encrypted. Additionally, passwords are never stored on a workstation or server in cleartext.

-

Every user has a password and every service has a password.

-

The only entity that knows all passwords is the authentication server. This authentication server operates under considerable physical security.

A simple diagram representing the Kerberos authentication scheme is given below:

+-------------------------------------------------------------+

| |

| |

| (7) |

| +---------------------+ | (8)

| | Kerberos |------|-------------------------+

| | Ticket Granting | | |

| +---------------->| Server (TGS) |<-----|-----------------+ |

| | +---------------------+ | (6) | |

| | | | |

| | | | V (5) (9) (11)

| +-----------------+ | +-------------------------+ (10) +-------------+

| | Kerberos | | | Workstation |-------------->| Server |

| | Database | | +-------------------------+ +-------------+

| +-----------------+ | ^ | ^

| | (3) | | | |

| | +---------------------+ | (4) | | |

| | | Kerberos |------|-----------------+ | |

| +---------------->| Authentication | | | |

| | Server |<-----|-------------------------+ |

| +---------------------+ | (2) | (1)

| | |

| | |

| | |

+-------------------------------------------------------------+ |

Kerberos Key Distribution Service V

+-----------------------+

| User |

+-----------------------+

Figure: Kerberos authentication scheme.

Implementation Process

From the text, the numbered steps, 1 to 11, in the figure do the following:

-

You, the user, walk up to a workstation and login. You enter your login name in the response to the normal UNIX

login:prompt. -

As part of the login sequence, and before you're prompted for your password, a message is sent across the network to the Kerberos authentication server. This message contains your login name along with the name of one particular Kerberos server: the Kerberos ticket-granting server (TGS).

message = { login-name, TGS-name }Since this message only contains two names, it need not be encrypted. Names are not considered secret since everyone has to know other names to communicate. You need to know other login names to send mail. You have to know the names of the different network services, to use a particular service. We'll see as we progress through the steps that follow that names are the only entities exchanged in cleartext between the workstation and Kerberos. Everything else is encrypted.

-

The authentication server looks up your login name and the service name (TGS) in the Kerberos database, and obtains an encryption key for each. The encryption keys used by Kerberos are one-way encrypted passwords, similar to what is stored in the password field entry of the normal UNIX password file.

-

The authentication server forms a response to send back to the login program on the workstation. This response contains a ticket that grants you access to the requested server (the TGS). The concept of a ticket and what makes up a ticket is central to the Kerberos system. Tickets are always sent across the network encrypted--they are never sent in cleartext. The ticket is a 4-tuple containing

ticket = { login-name, TGS-name, WS-net-address, TGS-session-key }(In addition to the fields mentioned above, they also contain a time stamp and an expiration date.) The

WS-net-addressis the Internet address of the workstation. TheTGS-session-keyis a random number generated by the authentication server. The authentication server then encrypts this ticket using the encryption key of the TGS server (which is obtained in step 3). This produces what is called a sealed ticket. A message is then formed consisting of the sealed ticket and the TGS-session-keymessage = { TGS-session-key, sealed-ticket }This message is then encrypted using your encryption key--your encrypted password, which is contained in the Kerberos database. Note that the TGS session key appears twice in the message: once within the ticket and again as part of the message itself.

-

The

loginprogram receives the encrypted message and only then prompts you for your password. This cleartext password you enter is first processed through the standard UNIX's encryption key, is used to decrypt the message (TGS session key and sealed ticket) that was received. Your cleartext password is then erased from memory. All that the workstation has now is a sealed ticket that has been encrypted using the TGS encryption key along with a TGS session key. This sealed ticket is incomprehensible to the workstation since it was encrypted using the TGS encryption key, that is only known to the TGS and Kerberos. The TGS session key is comprehensible to the workstation, but it is just some random bit string that the authentication server created.At this point the workstation software saves a copy of the sealed ticket and the TGS session key. Every workstation contains similar information: a sealed ticket for the ticket-granting service along with the corresponding random TGS session key. Even though all the sealed tickets are encrypted using the same encryption key (that of the ticket-granting server), since each ticket contains the name of the user the ticket was granted to, the workstation address, along with different random TGS session key, each is different.

Now consider the scenario when you request some network service. You might want to read your mail from the mail server, print a file on a print server, or access a file from a file server. We'll call the requested server the end-server, to differentiate it from the Kerberos ticket-granting server and the Kerberos authentication server described above. Every service request of this form requires first obtaining a ticket for the particular service. To obtain the ticket, the workstation software has to contact the Kerberos ticket-granting server. The following steps, however, are transparent to you when you access the service. This was a goal of Kerberos.

-

The workstation builds a message to be sent to the ticket-granting service. This message is a 3-tuple, consisting of

message = { sealed-ticket, sealed-authenticator, end-server-name }The authenticator is created by the workstation software, and is a 3-tuple consisting of

authenticator = { login-name, WS-net-address, current-time }To seal the authenticator, the workstation encrypts it using the TGS session key that it obtained in step 5. This message is sent to the ticket-granting service. Note that the first two elements of the message are encrypted (sealed) and the last element is a name that need not be encrypted.

-

The ticket-granting service receives the message and first decrypts the sealed ticket using its TGS encryption key. Recall that this ticket was originally sealed by the Kerberos authentication server in step 4 using the same key. From the unencrypted ticket the TGS obtains the TGS session key. It uses this session key to decrypt the sealed-authenticator. There are multiple items for the TGS to check for validity: the login name in both the ticket and the authenticator, and the TGS server name in the ticket. It also compares the network address in the ticket, the authenticator, and in the received message, and all must be equal. Finally, it compares the current time in the authenticator to make certain the message is recent. This requires that all the workstations and servers maintain their clocks within some prescribed tolerance. (Some of them are described in the text.) The TGS now looks up the end-server-name from the message in the Kerberos database, and obtains the encryption key for the specified service.

-

The TGS forms a new random session key and then creates a new ticket based on the requested end service name and the new session key.

ticket = { login-name, end-server-name, WS-net-address, new-session-key }This ticket format contains the same fields as the one we showed in step 4 earlier. We have just labelled the session key with the qualifier "new" to differentiate it from the TGS session key that was created by the Kerberos authentication service. This ticket is sealed using the encryption key for the requested end server. The TGS forms a message and sends it to the workstation.

message = { new-session-key, sealed-ticket }This message is then sealed using the TGS session key that the workstation knows, and sent to the workstation.

-

The workstation receives this sealed message and decrypts it using the TGS session key that it knows. From this message it again receives a sealed ticket that it cannot decrypt. This sealed ticket is what it has to send to the end server. It also obtains the new session key that it uses in the next step.

-

The workstation builds an authenticator

authenticator = { login-name, WS-net-address, current-time }and seals it using the new session key. Finally, the workstation is able to send a message to the end-server. This message is of the same format as the message it sent to the TGS.

message = { sealed-ticket, sealed-authenticator, end-server-name }This message isn't encrypted, since both the ticket and authenticator within the message are sealed, and the name of the end server isn't a secret.

-

The end-server receives this message and first decrypts the sealed-ticket using its encryption key, which only it and Kerberos know. It then uses the new session key contained in the ticket to decrypt the authenticator and does the same validation process that we described in step 7.

This is the flow of Kerberos scheme. It does not provide some of the properties that are described in the text. Further reading is highly encouraged. Refer to page 434 of text.

Programs

Remote Utils

- Program

- Output

/*

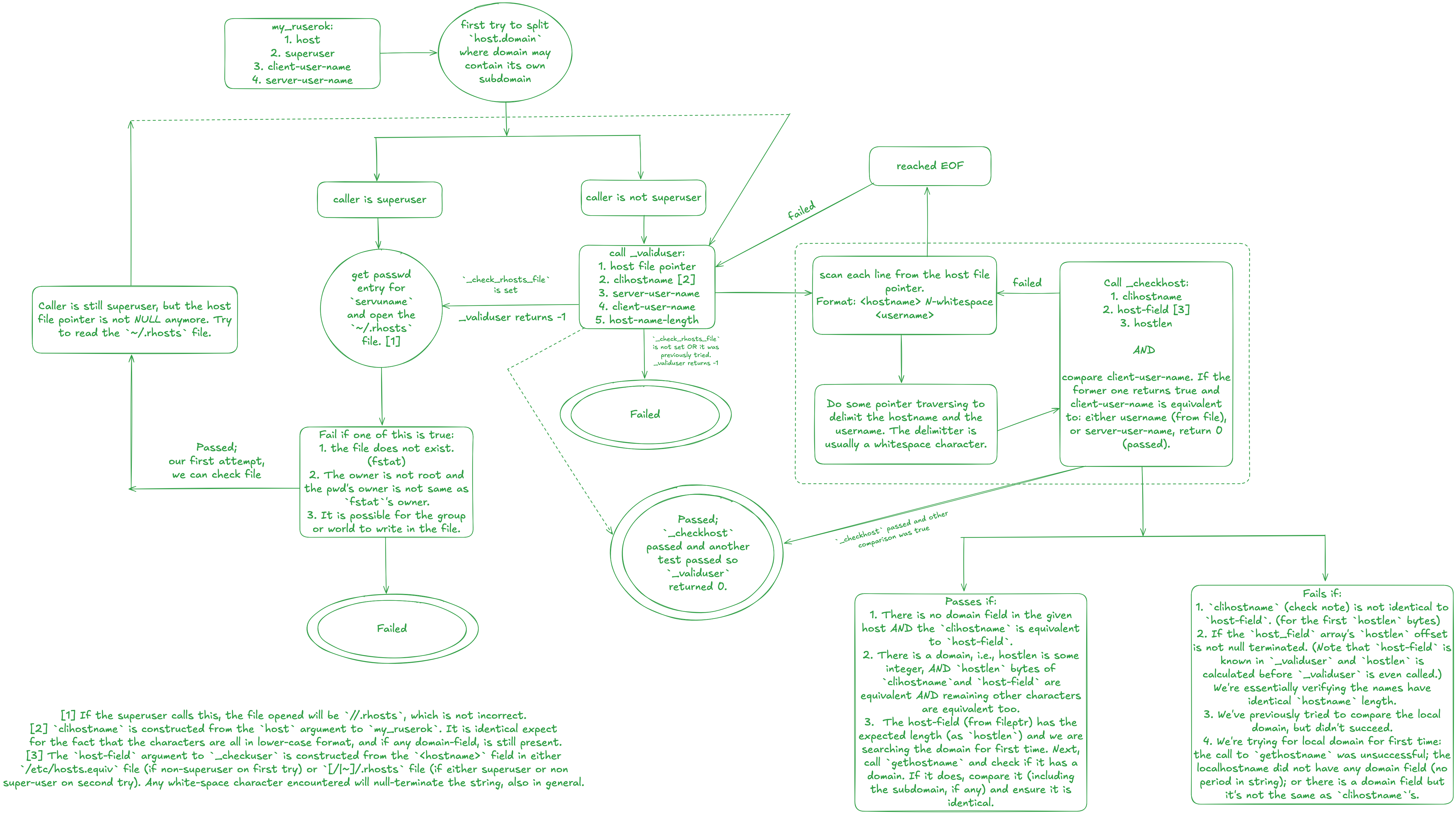

* There are some things to consider when talking about the authentication steps that was in use in networking.

* We have to understand some terminology as well.

*

* 1. client-user-name: The name of the user on the client's system making the request.

* 2. server-user-name: The name of the user on the server's system.

*

* There were multiple server programs that were available in older systems. Some of the programs that were defined are:

*