Interprocess Communication

Programs

File Record Locking

- Program

- Output

Pipe

- Program

- Output

Pipes Client Server

- Program

- Output

Pipe Stdio Lib

- Program

- Output

Fifo

- Program

- Output

Stream Messages

- Program

- Output

System V IPC

- Program

- Output

Multiplexing Messages

- Program

- Output

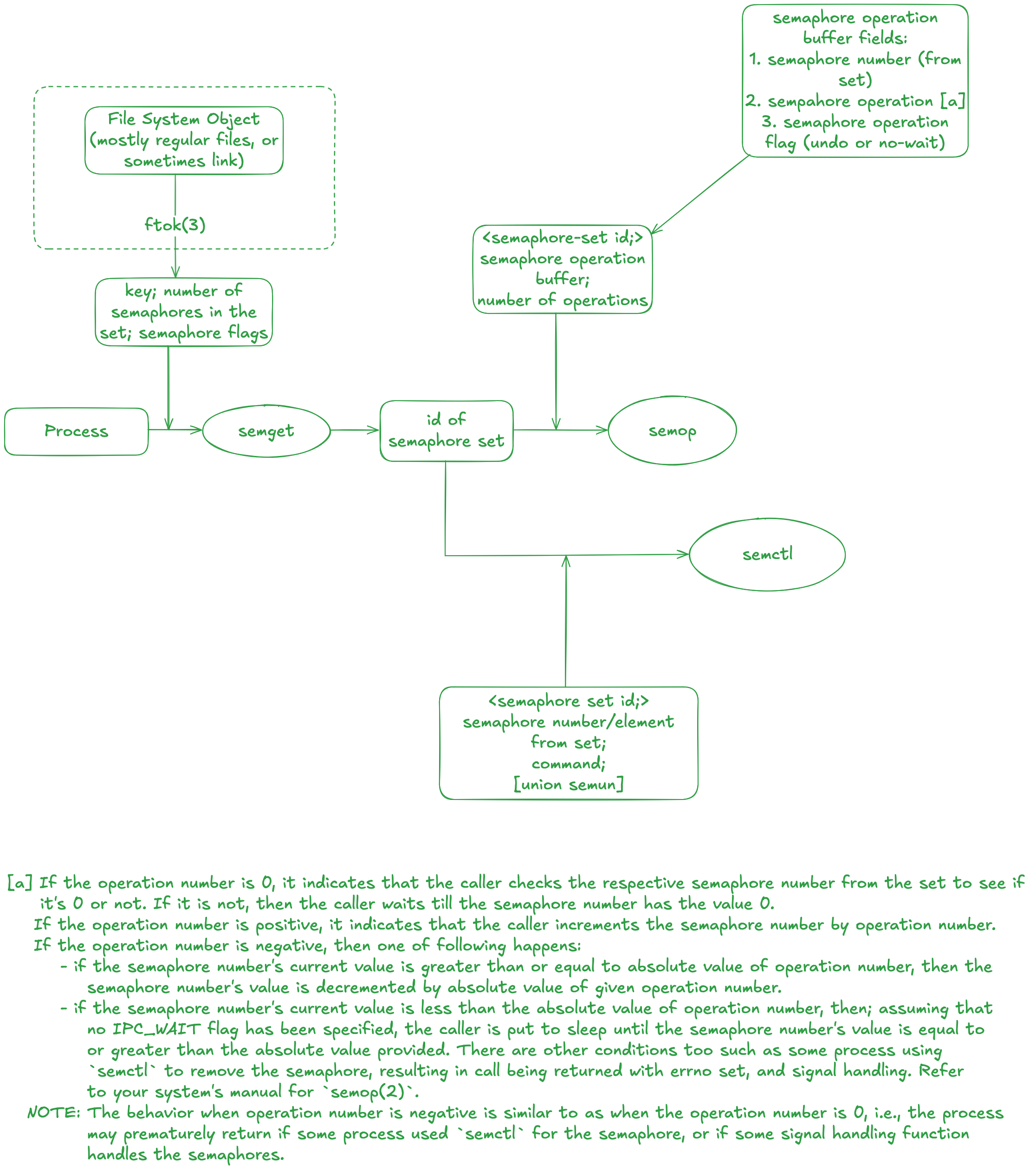

Semaphores

- Program

- Output

Shared Memory

- Program

- Output

Multi Buffer

- Program

- Output

Exercises

Question 3.1

Implement one of the filesystem based locking techniques from Section 3.2, say the technique that uses the link system call, and comapre the amount of time required for this, versus actual file locking.

- Answer

- Program

Needless to say, the provided program is not perfect nor is it production-ready. For instance, notice that we open the temporary unique file (the lock file is linked to this temporary file) is opened using the flag O_CREAT and O_EXCL. As stated in the link(2) manual page, the new link that is made copies the file system object's attributes to the new file. This means that if a runnning process was interrupted (like a signal such as SIGINT) and the process terminated before unlinking the lock file, then subsequent processes attempting to create a link fails as the file already exists. The temporary file is ofcourse present, but the link fails as the file already exists. Interested reader can modify this program such that before attempting a link to the lock file, check if it already exists, and try to read the PID of process that previously acquired that lock. Next, check if the process exists through kill(pid, 0). If it does not, just remove the file and then attempt to link the temporary file.

Also, this is sort of "exclusive lock." Unlike shared locks, which can be acquired by mulitple processes, this form of lock is limited to one process at a time. Unless the process unlinks the lock file, no other process can acquire our custom lock. Finally, a "timeout" logic exists such that given a positive non-zero timeout, the process checks if the lock can be acquired within that time. If the timeout is zero, it indicates a non-blocking call and immediately returns upon failure to acquire lock, and any negative timeout value indicates an indefinite blocking call.

As for the second part of the question, it's not shown here as the provided program does more than lock and instantly unlock the file. One could simply take the two functions: lock and unlock and then test it out with the record locking functionality provided by the system. Do note that Linux provides the functionality for "open file description lock". I'll explain this in brevity in the next paragraph.

The record locking functionality provided by historical UNIX variants are associated with the process, not the file description entry. Recall that a file descriptor is a per-process table which refers to an entry in the system-wide file description table. Each entry in this [system-wide] table contains the following attributes:

- Current file position or the file offset.

- File access mode;

openflags. - Reference count, an integer referring to how many file descriptors (from all processes) currently refer to this description.

- Pointer to inode table entry. (anonymous inode entry for non-persistent files such as unnamed pipes)

- File lock status. See include/linux/fs.h file and refer to

f_lockmember.

Given all this information, we can now start to discuss what are some potential problems. Traditional UNIX did not impose the lock status on open file description table. The lock was associated with the process and the inode. The [historical UNIX] kernels would only record which process has a lock on which inode. Furthermore, which could also be considered a flaw, whenever the descriptor for a file which contained a lock was closed; it would remove the entire lock from the file regardless of whether other descriptor(s) exists for the same file. This is mentioned in the fcntl(2) manual as well:

If a process closes any file descriptor referring to a file, then all of the process's locks on that file are released, regardless of the file descriptor(s) on which the locks were obtained. This is bad: it means that a process can lose its locks on a file such as /etc/passwd or /etc/mtab when for some reason a library function decides to open, read, and close the same file.

Another flaw mentioned is in regards to a process in a multi-threaded environment. Threads in a process share locks. A multi-threaded program can't use traditional record locking to ensure that threads don't simultaneously access the same region of a file.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <errno.h>

#include <time.h>

#define LOCKPATH "/tmp/mylock.tmp" /* actual lock file */

#define TEMPPATH "/tmp/" /* per-process: `/tmp/<pid>` */

Question 3.2

Under System V Release 3.2 or later, write a program that uses record locking. Use the program to verify that advisory locking is only advisory. Then modify the file's access bits to enable mandatory record locking and use the program to verify that locking is now mandatory.

- Answer

- Program

The latter part of the question is more complicated than it seems on newer systems. In fact, Mandatory File Locking For The Linux Operating System provides deeper insights into why mandatory locking causes more problems than provide solutions. Moreover, under BUGS section for fcntl(2) manual on Linux, it explains how a race condition is possible when mandatory locking is set on a file. Similary the subsection "Mandatory Locking" in the DESCRIPTION for the manual asserts that mandatory locking support has been removed since Linux 5.15. For Linux versions prior to this, a filesystem mounted from mount(8) can only support mandatory locking provided the -o mand flag was used for the respective filesystem. This means, apart from the legacy requirement; setting the lock file's group execute bit off and set-group-ID bit on, a few more steps needs to be done before the file can support mandatory locking from the Linux kernel.

The program I wrote illustrates that a lock to a file is only limited to the process. The parent process opens the file and applies a exclusive lock on a region in that file. It proceeds to fork and create a new process. Since the child inherits the lock for files opened by the parent, I've closed the file and reopened. This ensures that the child process has it's own file description. The child process writes to the file to illustrate that it is indeed only advisory lock. The write call is successful in the child process. Also, we could also say that the child process in this case is the non-cooperating process.

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <sys/wait.h>

#define LOCKFILE "/tmp/myrecord.lock"

Question 3.3

Why is a signal generated for the writer of a pipe or FIFO when the other end disappears, and not for the reader of a pipe or FIFO when its writer disappears?

- Answer

There isn't any explicit signal generation for a process who is reading from a pipe or FIFO because reading a pipe whose write end has been closed causes the read(2) to return 0. This is not the case when there is a writing end but the pipe is empty, where the call is blocked unless fcntl is used to enable non-blocking I/O (O_NONBLOCK). If the non-blocking flag is enabled, then read(2) returns -1 (given that there is a writer but the pipe is empty) and set errno to EAGAIN.

SIGPIPE is an indicator to the calling process that an attempt was made to write to a pipe which doesn't have a reader. The process receiving this signal terminates by default, but appropriate handler can be installed. The call to write(2) will return -1 and set errno to EPIPE whenever the SIGPIPE signal is ignored. This is more of a design choice as the reader need not receive any signal simply cause one of a pipe it is reading has now been closed. From the readers perspective, a positive return value indicates the number of bytes read from the pipe, a negative value indicates that some form of error has occurred (one of which being an empty pipe for non-blocking I/O), and a return value of zero indicating that no writers are present.

Question 3.4

Use the multiple buffer technique in Section 3.11 to write a program that copies between two different devices--a disk file and a tape drive, for example. First measure the operation when only a single buffer is used, then measure the operation for different values of NBUFF, say 2, 3, and 4. Compare the results. Where do you think most of the overhead is when multiple buffers are used?

- Answer

Copying from one device to another is a low-level operation and is something I can't do for now. Instead, let's discuss the program that was shown in Section 3.11. The program in question utilizes two IPC mechanisms provided by System V: shared memory and semaphores. The program has client and server, where client sends the name of the file to the server and server opens the file and sends the content of the file back to the client. A more sophisticated sequence is described below:

-

The server is first instantiated. Before the server is in the "waiting" state, it creates

NBUFFshared memory segments, each segment capable of storingsizeof(Mesg)bytes (and attaches them too), along with creating two semaphore sets;clisemandservsem. We'll discuss the internals of semaphores later. But it should be known that the client semaphore is initialized to 1 whereas the server semaphore is initialized to 0. The server semaphore is initialized as such to ensure the server process will be in "waiting" state until the client writes data (the name of the file to open) to the shared memory segment. -

The client will be instantiated while the server is in the waiting state. The client will fetch the shared memory segment and attach them to the current process. The semaphore set is also fetched. Before the standard input stream is read using the

fgetscall, the client process callssem_wait--a custom function--to decrement the semaphore value (which was initialized by the server as 1), essentially asserting the fact that any other process which wishes to use this semaphore (if such exists) will end up waiting. The filename from the standard input stream is read, and is stored in the shared memory segment (the first one, if there areNBUFFsegments). After doing so, the client calls another custom function,sem_signal, to increment the server semaphore, essentially "waking" up the server. Also, the client callsem_waiton the client semaphore, so it will be in "waiting" state. -

The server wakes up and first up null terminates the data in the shared memory segment which was written by the client. This operation is sort of redundant as the client already null terminates the data. Nevertheless, an attempt at

opening the file is done with the flag of0which means the file will be opened in read-only mode. The next point will mention how the interaction will take place for a successful call but we'll first talk about the unsuccessful call. If the call returned-1, first we write the error message to a local variable and later concatenate that with the filename that was written by the client in the shared memory segment. We callsem_signalto wake up the client and the client will eventually read the error message. The client is not aware that it needs to terminate. The server will now set themesg_lenof next shared memory segment to0and againsem_signalthe client semaphore. The client reads the field and terminates when it is less than or equal to 0. -

Upon a successful call to

open, the server process now callssem_signalNBUFFtimes on the server semaphore. This is done to fill the buffers immediately. Each iteration inside the for loop (the loop is iteratedNBUFFtimes) decrements the server semaphore value by 1, readsMAXMESGDATAbytes from the file andsem_signalthe client semaphore, so the client can read the data. If a file which has data >NBUFF * MAXMESGDATA, then the shared memory segment is cycled back. -

Finally, the shared memory segments are detached and the semaphores are closed. The client and server then terminates.

To ensure that premature termination does not cause any lingering semaphore set, we use the SEM_UNDO flag which tells the kernel to adjust the semaphore values if such termination was to take place.

Sempahores are a synchronization primitives. In this example, the use of sempahore is to ensure the shared memory is accessed as desired; client first writes to the shared memory segment before the server reads it, and such. This does not imply that creating and initializing the semaphores are free from any potential race condition. When achieving a task requires multiple system calls (like semget and semctl), it means there is a possibility for a race condition as discussed on sem_create function in the sempahore.c source file. System V semaphores are a set which contains members whose value are non-negative. This allows us to create a semaphore ID (through semget) and mention the total number of members in that semaphore set. In our case, we created a sempahore set which has 3 members; the first one is the actual semaphore used by the process to synchronize, the second one is used as a process counter (the processes that opened this particular semaphore), and the third one is used to eradicate any possible race condition that may occur during the creation of sempahore set itself.

Returning back to the question, I'm not particularly informed when it comes to file in the /dev directory. Also, I'm not certain about how interaction takes between the device driver and the actual device on macOS. For instance, the system would use a driver when writing to a file in a "disk" device and use another driver to read from a file in a "tape drive" device. Apple has been known to not properly document their drivers and let the hackers attempt to reverse engineer it; such as team Asahi Linux. Maybe I'm dive into this rabbit hole later, but not right now.

As for the last part of the question, I could only guess that the only overhead that arises in a multiple buffer scenario is when doing operation such as read(2) and write(2). When creating a shared memory segment, the kernel allocates the sufficient bytes from the physical address and then maps it to virtual address. Each process that maps to this memory segment has its own virtual address space. Consider these steps; which are mentioned in the text, to copy file from a client to a server:

- The server reads from the input file. Typically the data is read by the kernel into one of its internal block buffers and copied from there to the server's buffer (the second argument to the

readsystem call). It should be noted that most Unix systems detect sequential reading, as is done by the server, and try to keep one block ahead of thereadrequests. This helps reduce the clock time required to copy a file, but the data for every read is still copied by the kernel from its block buffer to the caller's buffer.- The server writes this data in a message, using one of the techniques described in this chapter--a pipe, FIFO or message queue. Any of these three forms of IPC require the data to be copied from the user's buffer into the kernel.

- The client reads the data from the IPC channel, again requiring the data be copied from the kernel's IPC buffer to the client's buffer.

- Finally the data is copied from the client's buffer, the second argument to the

writesystem call, to the output file. This might involve just copying the data into a kernel buffer and returning, with the kernel doing the actual write operation to the device at some later time.

without the use of shared memory. Shared memories program does the following instead:

- The server gets access to a shared memory segment using a semaphore.

- The server reads from the input file into the shared memory segment. The address to read into, the second argument to the read system call, points into shared memory.

- When the read is complete the server notifies the client, again using a semaphore.

- The client writes the data from the shared memory segment to the output file.

The interaction takes place as follows:

+---------+ +- - - - - - - -+ +---------+

| client |<------->| shared memory |<--------->| server |

+---------+ +- - - - - - - -+ +---------+

| ^

| |

+---+---------+-----+

+---------+ | | | | +---------+

| output |<------+---+ +-----+---------| input |

| file | | | | file |

+---------+ +-------------------+ +---------+

kernel

Figure: Movement of data between client and server using shared memory

And finally, the author mentions that despite the data only being copied twice, both of these copies probably involve the kernel's block buffers.

Even though I failed to answer this question, I've come across a rather interesting program found in the author's relatively new text: Advanced Programming in Unix Environment. This program demoonstrates how a user can allocate shared-memory-like region through the use of mmap(2). Another program is also provided; cp.c, which copies file using mmap(2). There is a subtle yet fundamental differnce between how memory region is used. For copying, we need to ensure that the "dirty writes" are synchronized with the file mapped, copying the content from one file to another. The shared memory example uses /dev/zero to allocate memory that will be shared by the parent and the child process.

Attempting to mmap(2) a region of the file /dev/zero to the process's memory region will raise an error during mmap(2). The errno value set is ENODEV and the manual states for reasoning for this error as, "MAP_ANON has not been specified and the file fd refers to does not support mapping." This implies that we can't map region of /dev/zero. Needless to say, using MAP_ANON (or MAP_ANONYMOUS) flag and specifying fd as -1 solves this problem. Note that specifying MAP_ANON implicitly ignores the offset argument to mmap(2) call, as stated in the manual. Also for macOS specifc, the fd can either be -1 or any Mach VM flag defined in <mach/vm_statistics.h> header.

Question 3.5

What happens with the client-server example using message queues, if the file to be copied is a binary file? What happens to the version that uses the popen function if the file is a binary file?

- Answer

The behavior is sort of unstable when the client simply writes the data sent by the server (the binary file) to its standard output stream (It does display the content). But this was not the case when the cient writes to a regular file. The data copied by the client from the message queue was later tested with diff(1) and it showed that the input file and the new file was identical.

Similar thing for the popen(3) approach as well. I had the directory structure such that there were files: server.o, server, and server.c. Using the input file server.o wrote the content, albeit it was not readable (whoosh!), but the input file server did not result in anything. This is also what happened when doing the former approach; message queues only.

Getting back to the popen(3) one. I simply use the cat(1) command along with the input file that was sent by the client. Some changes were done to the message queue program to work with popen(3). These changes are mentioned below:

- Initialize a character array that will be used as command argument to

popen(3). The array could also be initialized with the string "cat ". - After fetching the input file name from the client, concatenate this to the character array we defined.

- Rather than using

open(2)to open the file (inO_RDONLYmode), we usepopen(3)with mode being "r", indicating we want the output of the command available to be read. - I've previously added the

stat(2)call to determine if the user requested to open a directory and act appropriately. For brevity, I've disabled this check. - Instead of using

read(2)to read the file content,fread(3)is used. The manual states that this call reads nitems object, each size bytes long.MAXMESGDATAwas set fornitemsand1for thesize. - Instead of

close(2),pclose(3)is used for file opened usingpopen(3).